The Gold Standard Explained

What is The Gold Standard? 💸

The gold standard is an important relic for investors to understand, in terms of how it came to be and why we left it behind. Humans have a long history of transacting in gold, and gold has often been deemed an unquestionable store of value during periods of inflation and recession. Many of the loudest critics of current financial infrastructure will cite the gold standard as the be-all end-all, arguing that our economic problems would be solved if we were to go back to it. Whether this claim is true or not is beside the point. We'll let you form your own opinion, but first, let's explore several key aspects of the gold standard.

First, we'll go over exactly what the gold standard is, how it works, and why we eventually went off it. Much of this is based in history, and will encompass how the gold standard started, bimetallism, the initial classic gold standard, its role during the world wars, the post-World War II Bretton Woods Agreement, and finally, the system's end when President Nixon decoupled the U.S. dollar from gold. Throughout, we will provide you with basic economic facts regarding what happens to interest rates, inflation, economic growth, and overall capitalism during gold standard regimes. Finally, there have been plenty of questions about how the gold standard might end up making a comeback, specifically in the form of a new currency proposed by BRICS. Let’s dive in.

The Gold Standard Explained

The gold standard is a currency system by which government-issued money is backed, at a fixed exchange rate, to gold. The gold standard was the primary monetary regime for a large part of the late 19th and mid-20th centuries. Benefits of the gold standard include interest rate stability, limits on government debt/spending, and lessened central control over the economy. The disadvantages include volatility in inflation, unpredictable business cycles, and massive storage and insurance costs. Despite recent news on BRICS and high inflation, the gold standard will not make a return, simply because of the unsteady impacts it can have on a global economy.

To explain the gold standard, we have to first understand central banks. A central bank is a government-run financial institution providing banking services to the government that created it, as well as other large commercial banks that need someone behind them. The central bank is responsible for conducting monetary policy and overseeing the stability of the economy/financial system. A common euphemism used for a central bank is the lender of last resort. If banks go under, the central bank can serve as a backstop to failing firms, which protects all parts of the economic value chain that is tied to that institution.

Through a dizzying array of financial transactions, the central bank can create and destroy money, change interest rates, and steer the economy towards goals of price stability and maximum employment. In the United States we have the Federal Reserve, while in Europe they have the European Central Bank. Other central banks of note include the Bank of London, Bank of Japan, and Bank of Canada.

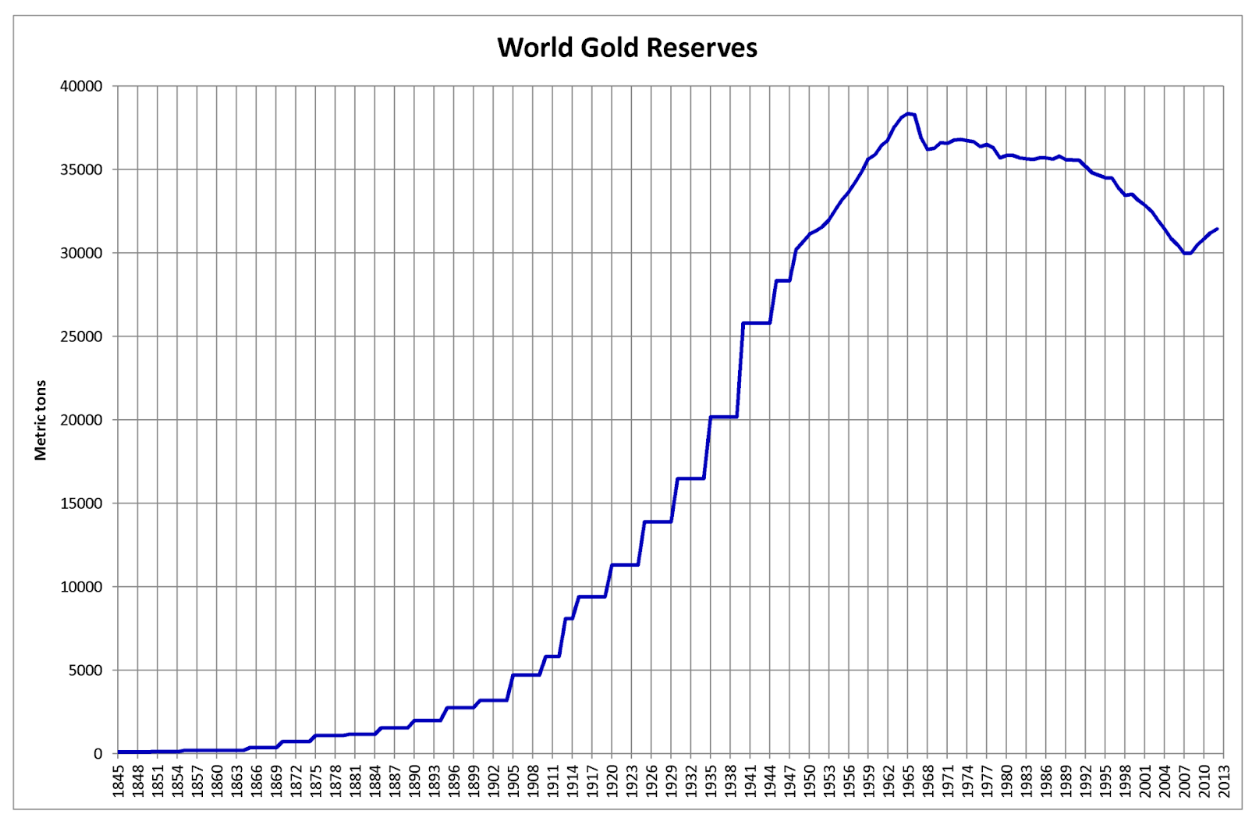

Over time, central banks repeat this process of financial wizardry, creating money and devaluing the existing currency. The gold standard was the initial fix to the classic financial problem that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. It required that central banks (and before that, all banks in general) exchange currency for a set amount of gold, at all times. Thus, gold reserves formed the most important base of the world currency system and were held in copious amounts by these central banks to facilitate transfers. The amount at which this exchange happened was predetermined, and the central bank both bought and sold gold for its currency at said price.

The amount of money a government could create, or debt it could take on, is thus limited by how much gold it has in reserves. If a country wanted to create more money, they would have to have more wealth enter the country in the form of gold, or currency that gets exchanged for gold. This only happens if there is a viable economic reason for it to do so. If they tried to create money without it, citizens and banks would panic, exchanging their dollars for gold until the gold ran out. Eventually, the central bank would have no more gold by which to exchange, and new money creation would not only stop, but the currency would be deemed worthless.

How Does the Gold Standard Work?

The gold standard works by way of the government/central bank "making a market" for its currency alongside its gold reserves. Any individual or bank could access this market and freely exchange their currency for gold and vice-versa. The gold standard effectively prevented governments from printing money out of thin air because if they did, they would have to have the gold to back it up. As gold is a scarce and supply-limited commodity, there was no way for the money supply to increase without gold or wealth accumulating in that country. Gold also formed the basis of interest rates, exchange rates, and international trade. Each is described below.

Interest Rates

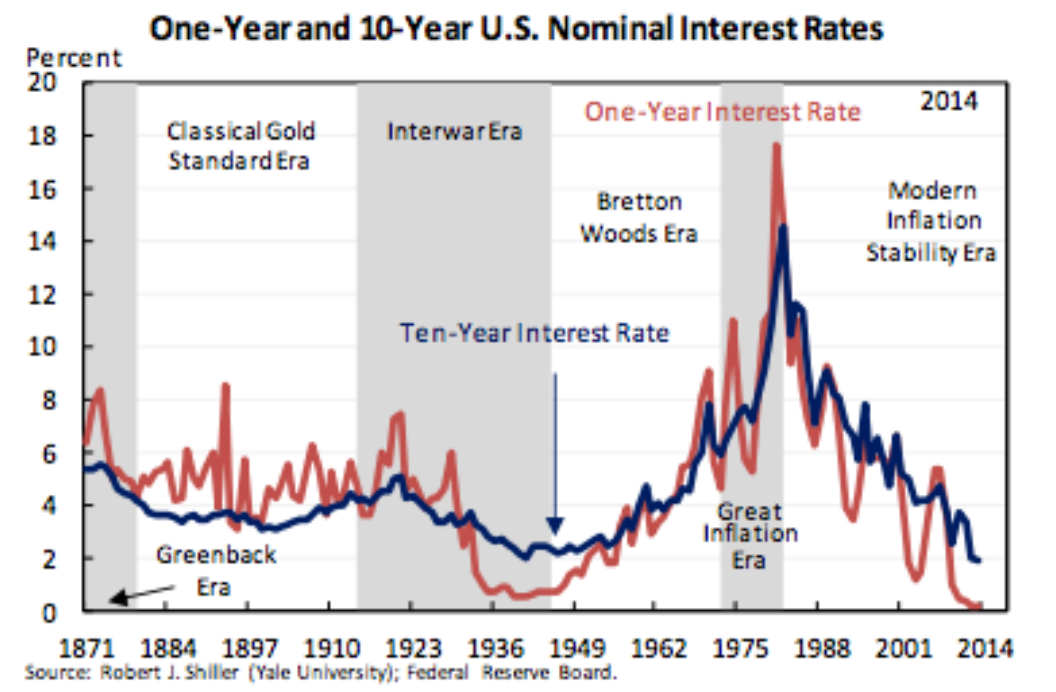

Under a gold standard regime, the rate of interest is determined only by the free market, one of the major advantages of this system. Interest rates become very stable because they reflect the choices of actors in the economy. An investor sets the floor on interest rates, selling an interest-producing investment (like a treasury) when their benefit does not outweigh the convenience of owning gold. An entrepreneur will do the opposite and buy the same interest-producing investment when they believe they can no longer use the gold to get a higher return. During periods under the gold standard, long-term interest rates were notably very stable, falling between 3-5% at all times.

Exchange Rates

In a gold standard regime, exchange rates are fixed based on the price of gold in relative economies. If the United States offers 1 Troy oz. of gold for $20 and Britain offers the same Troy oz. for £40, the exchange rate between the two countries will be 2:1 so that the fixed amount of gold received will not differ between the U.S. and Britain.

International Trade

A gold standard regime will also help control a country's imports and exports. Since international trade settles in gold, if a country exports too much, lots of gold will flow into the country. This will increase the money supply, leading to inflation. This inflation will be domestic only, and then make international goods marginally more attractive for purchasers in the home country. Conversely, when gold leaves the country, the money supply contracts and the effect is reversed. This self-correcting mechanism, known as the Price-specie flow mechanism, helps balance trade imbalances between countries.

History of the Gold Standard

After the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, congress passed their first monetary act, the Coinage Act of 1792. This created the U.S. Mint and the first iterations of currency. Original coins were issued in both gold and silver, a practice known as bimetallism. Coins were created with an equivalent value of gold or silver in all so that validity and worth could not be questioned - it was literally engrained in the money. However, during the period preceding the civil war supply and demand in silver and gold varied greatly, causing the government to change the amounts of the precious metal that went into coins. This led to differences in the worth of different issues of coin, and promoted what is known as Gresham's Law.

Fast forward 75 years, and growing tension between the Union and Confederacy led to the first real abandonment of the gold standard. In order to pay for the coming war, policymakers in the Union passed the Legal Tender Act, which marked the first use of the terms we all know so well today:

THIS NOTE IS LEGAL TENDER FOR ALL DEBTS, PUBLIC AND PRIVATE.

Here marked the first iteration of our current monetary system. Currency was backed by nothing but the full faith and credit of the United States government. There wasn't enough gold or silver in the United States for the government to issue all 450 billion new dollars under the bimetallic system, so they got rid of it. Paper money and deposit notes (circa 1861) became standard practice into and through the civil war. For all intents and purposes, this worked well but left the post-civil war government with 2.5 billion (which was a lot back then) in debts and 80% inflation.

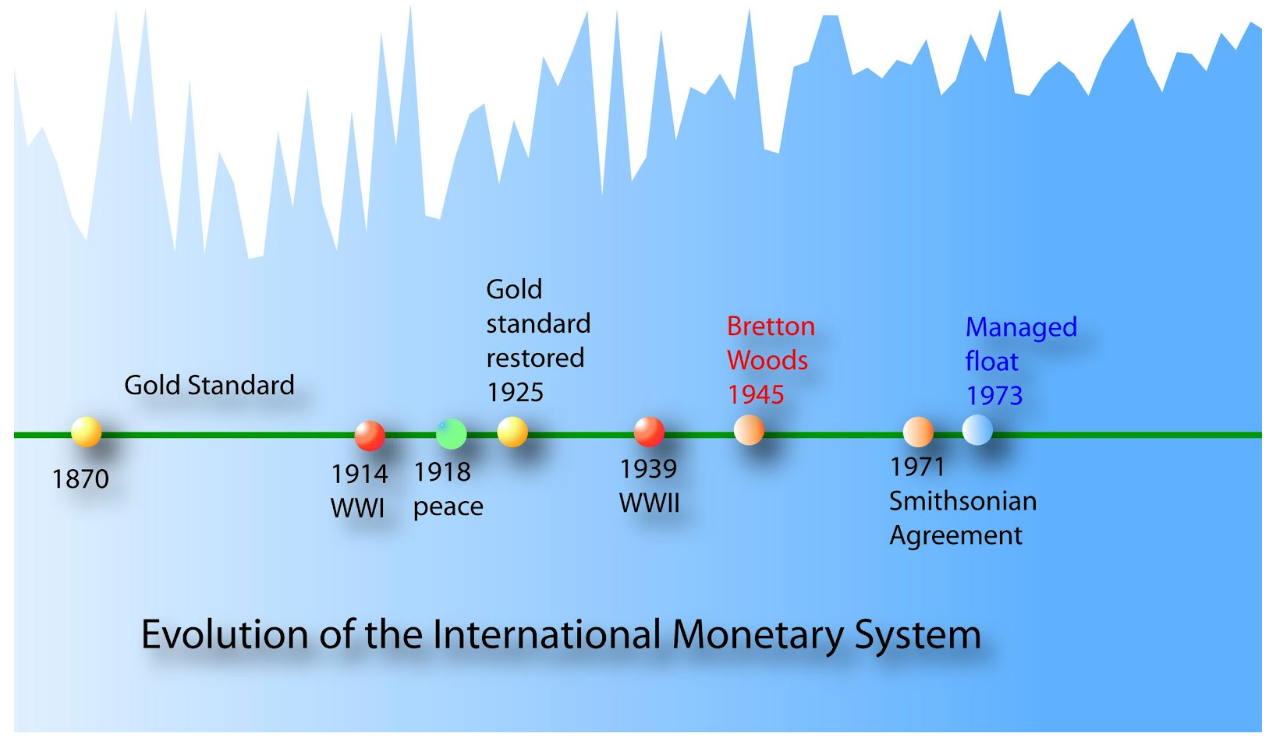

After an ensuing post-war depression due to the debt and more silver shortages, Congress decided it was time to go back to a backed currency system for good. The Specie Payment Resumption Act was passed in 1875 and the period known as the Classical Gold Standard began. Gold was agreed upon by all large central bankers to be the unit of transaction internationally, and most currencies were pegged to gold or a larger currency that was. This period lasted until, you guessed it, another world war.

World War 1 proved even more expensive than the civil war, and all large global players took part. There wasn't enough gold in the world again to back all the new money needed for weapons, soldiers, and the like. Governments put in wartime restrictions on shipping gold overseas and once again, removed the convertibility to gold of paper money. As the end of the war approached, countries gradually returned to the gold standard system of before, especially in the United States, where WW1 provided a boom to the economy. However, certain nuances also made their way into new gold standard laws. For example, the passage of Woodrow Wilson's Federal Reserve Act gave the government the ability to control interest rates, and required that new currency created (known as Federal Reserve Notes or Dollars) be backed by gold at a rate of 40%. The idea was to both control the issuance of new paper while also allowing for more flexibility in steering the economy. This led to some of the fastest periods of economic growth in U.S. history, known as the Roaring Twenties.

During the roaring twenties, gold became a scarce commodity sometimes only available in rich countries. As such, 1925 marked another switch in the monetary regime. In 1925, the Gold Exchange Standard was passed, where many currencies were still pegged to gold, but nations had the option to not hold gold reserves and instead attach their currencies to either the Federal Reserve Note (Dollar) or British Pound. The U.S. and Great Britain were required to always hold gold, being they were the two largest and most powerful economies at the time. This was short-lived as well, as the Great Depression caused massive gold outflows from Britain (who canceled their redeemability) and the inability to print money in the U.S. due to the 40% limit led to gold hoarding and deflation. It is well recorded that the gold standard was one part of the severity of the late 1920s and early 1930s, both in the U.S. and abroad.

In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt nationalized gold as part of his massive economic overhaul, making it illegal for private citizens to own it or exchange it for their dollars. The Federal Reserve became the only American institution with the privilege of gold ownership, and it only transacted with other central banks as a means of international finance. He also ended the decades-long international agreements that required transactions be settled in gold. They could now be settled in dollars as well. Gold was pegged to a dollar price of $35 an ounce, but only the aforementioned international central banks had access to this market. This was ratified officially at the Bretton Woods Agreement in the summer of 1944. Under Bretton Woods, all world currencies had to be convertible to U.S. dollars at a predetermined rate, and those U.S. dollars would stay pegged to gold at $35 an ounce.

Why We Went Off the Gold Standard

Bretton Woods proved efficient until 1971, when due to decades of trade deficits and growth in global trade, the U.S. no longer had enough gold to fulfill all its obligations to foreign central banks (in this case obligations and dollars are synonymous). The period of the "Great Inflation" during the mid-sixties through early-eighties caused an increased interest in the convertibility of U.S. dollars to gold. The gold wasn't there, and since gold prices were not allowed to float, intense stress was seen not only on the Federal Reserve but within the U.S. economy. There just weren't the resources to fulfill all the obligations we had given the world, and the $35 dollar gold price was a screaming deal that needed to be adjusted up due to 3 decades of strong economic growth. Dollars were sensationally overvalued, which further festered American trade deficit problems.

Finally, President Nixon decided that to continue to stimulate global trade, it would have to happen with an unrestricted reserve currency. In 1971, swiftly and decisively, the United States said it would no longer honor its gold conversions. This marked the end of the gold standard and set forth the monetary system we use today. Known as the Managed Float, currencies are backed solely by the assets and faith of the government that issues them. Supply and demand, economic conditions, and interest rates determine the value of currencies, and governments are free to create or destroy as much money as they see fit.

Is the Gold Standard Coming Back?

In short, no - the gold standard is most certainly not returning. While the gold standard has distinct advantages that we have discussed, it also has some very notable disadvantages. The first disadvantage being the fact that prices are fixed on the economy's most important commodity. While some might argue this is a beneficial feature that safeguards people's wealth, it's actually a significant drawback. If gold and the dollar are convertible at the same rate forever, no economic growth will show up in that exchange. Rather, as former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has illustrated, the volatility one might see in the price of gold will simply be cast out to the price of goods and services in the economy. This leads to out-of-whack expectations by consumers and businesses and makes economic cycles more volatile. We notice convincingly that during periods of the gold standard, both inflation and GDP growth are more volatile.

A second major downfall of a gold standard system has to do with gold itself. Gold, outside of the value we have assigned it, has very little utility. Roughly 78% of the world's gold is used for jewelry alone. Under a gold standard, a huge amount of economic waste occurs in the trade, extraction, storage, and insurance of gold reserves. Money can also only be created when gold is found, mined, or imported from another country. While this might reassure folks in the value of their currencies in the short run, it also sets the stage for massive levels of international discrepancy. Due to the specie-flow mechanism, countries that need extra economic boosts or help won't get it, and everything will be in balance based solely on the amount of gold moved between borders.

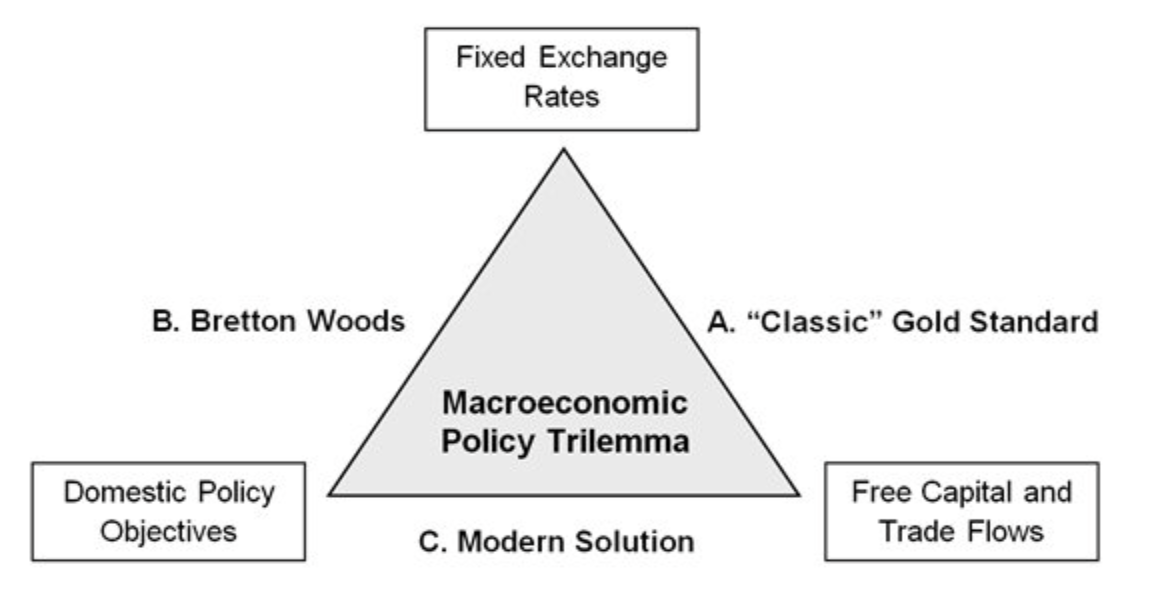

Lastly, the most important hindrance of a gold standard system is the inability for governments and central banks to conduct independent monetary policy. While one of the big selling points to a gold standard is controlled money supply, investors would best understand the ways in which a gold standard can encourage deflation. If a central bank under a gold standard wants to spur the economy, they will lower interest rates. However, lower interest rates will cause capital (and gold) to leave the country. This will shrink the money supply and cause deflation. Deflation will halt the economy in its tracks and render the action of the central bank worthless. This could lead to self-reinforcing recessions that never end, massive bank failures, and a select few "gold-rich" countries that can hoard the monetary reserves that the rest of the world needs to get going again. As we are well aware, economies are different and unique, and what works for one likely won't work for another. The self-correcting features in a gold standard regime make it impossible to tailor policy to your own domestic objectives. One of the greatest paradigms in all of finance is that a global economy can have only 2 of the following 3 things:

Recently, a group of nations has been pursuing a new currency, colloquially known as BRICS. The BRICS nations hope to bring the gold standard back by way of a gold (or other commodity-backed) form of money. This money will be digital and used for trade in the eastern half of the world. It could hypothetically be backed by multiple commodities, the most likely being Russian Oil, Chinese Gold, or South African Diamonds. While we note it is an interesting idea, the studious investor would recognize that the same problems will always apply.

A Final Word on the Gold Standard

The gold standard is a monetary regime where currencies are backed by gold. No new money can be created without equivalent gold reserves. The gold standard was the primary policy for the world financial system from 1870-1970, only ceasing during wars. The gold standard has been directly linked to worsening many financial crises, so much so that the world will likely never go back to it.

Okay team, that's all I've got for you on the gold standard. Now you know exactly what it is, how it works, and why we left it behind. I'll leave you with my 3 core investing philosophies - the things that underpin everything I believe about capital markets and financial success. Feel free to share them with a friend or two.

- Economics, politics and emotions have no place in investment decision making.

- The best time to get started was yesterday, the second best time is today.

- Buy U.S. stocks and never sell them.

And with that, we'll see you in the next Dispatch.

Comments ()